Optical Activity and Rotatory Dispersion

Optical activity is a phenomenon where certain molecules rotate the plane of polarized light. While this basic definition is widely known, the underlying quantum mechanical and electromagnetic mechanisms reveal a fascinating interplay between molecular structure and light interaction.

When light interacts with chiral molecules, it induces both electric (

where:

The crucial parameter

Circular Birefringence and Its Electronic Origin

The mixed polarizability

The refractive indices for right (R) and left (L) circular polarization are:

where:

The rotation angle per unit length is:

At a quantum level, the mixed polarizability

This expression connects molecular electronic structure to circular birefringence through:

- Electronic transitions (

- Spatial arrangement of electrons (through

- Molecular chirality (required for non-zero

Wavelength Dependence and the Cotton Effect

The wavelength dependence of optical rotation becomes more complex near electronic absorption bands, leading to the Cotton effect. This phenomenon is described mathematically by the sum of two terms:

In this expression,

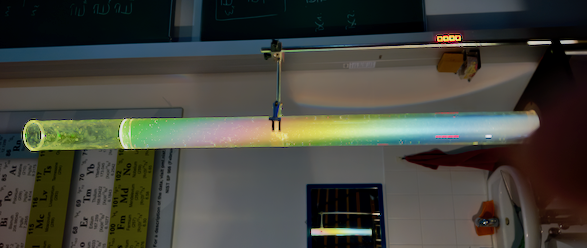

Sugar Solutions

In sugar molecules, the optical activity arises from their asymmetric carbon centers and specific electronic structure:

Coupled Chromophores: The oxygen atoms and hydroxyl groups create a network of coupled electronic transitions.

Helical Electron Displacement: During light interaction, electrons follow a helical path:

The colored scattering in sugar solutions results from three combined effects:

- Wavelength-Dependent Rotation: As light passes through a sugar solution, different wavelengths experience different amounts of rotation. This wavelength dependence follows a modified Drude equation:

where

- Differential Scattering: Different wavelengths scatter at different angles due to varying rotation angles. This creates a spatial separation of colors, as each wavelength emerges from the solution at a slightly different angle. The scattering angle

This relationship leads to a rainbow-like separation of colors in the scattered light.

- Multiple Scattering Effects: In real sugar solutions, light often undergoes multiple scattering events. The intensity of scattered light follows:

where

Temperature Effects

Temperature influences these processes through:

Molecular rotation rates:

Conformational distribution:

Applications and Practical Implications

Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for:

- Design of polarimetric instruments

- Industrial crystallization processes

- Chiral separation techniques

- Pharmaceutical analysis methods

The complex interplay between electronic structure, circular birefringence, and light scattering explains both the fundamental nature of optical activity and its practical applications in various fields.